Published in the Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans From Russia,

Vol. 14, No. 2 – Summer 1991, pp. 1 – 3.

Posted with permission of the AHSGR and of the author, May 22, 1996

(Oren Windholz of Hays, Kansas, gives dramatic evidence of what can happen when a simple letter is directed to the right person. It is hoped that such tactics will be useful to others researching ancestral villages.)

After the Romanian Revolution in December 1989, members of the Bukovina Society of the Americas had hoped that communications with the old country would improve. After World War II, the former crownland of Bukovina, the easternmost part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was incorporated into Romania and the Soviet Union. Pojana Mikuli is today in Romania; it is the ancestral village of my maternal grandparents. Letters had been exchanged between inhabitants there and friends we met in Augsburg when my wife Pat and I attended the 40th annual convention of the Association of Bukovina Germans (Landsmannschaft der Buchenlanddeutschen). It seemed improbable that I would be the first to receive a letter, since I had no personal contacts with anyone there.

Because of past success in writing blind letters to towns in Germany in order to locate relatives, I addressed two letters to Pojana Mikuli in March, 1990: one to the village priest and another to the mayor. On the envelopes I typed their titles, the town, and the country, using several spellings of each. Hoping to enhance my chances of being understood, I wrote the same short letter first in German, then below it in English, informing my anticipated recipients we had formed the Bukovina Society of the Americas and in July 1990 planned to hold our second annual convention. Further, I noted that my grandparents, surnamed Erbert and Fuchs, had been born in their village. I closed my letter with a request that they communicate with me and perhaps also send a picture of themselves and of their village.

Foreign mail is frequently delivered to my postal box, and one month later a letter arrived with a special “Herzlich Grüssen”” written below my address. In looking at the return address on the back I was indescribably thrilled to see Poiana Micului (Pojana Mikuli) written on it. After realizing the letter was not in German, I searched for someone to translate Romanian, based on my incorrect assumption. In the meantime, I tried to look up some of the words in a Romanian dictionary I had acquired. I found not a single one. A consultation with my former foreign language professor at Ft. Hays University soon revealed that the letter was written in Polish!

I had joked with my wife earlier, noting that even if my letter did not reach the mayor or the priest, maybe a postal clerk would get curious and forward them to someone. Sure enough, my new friend, Lukasz Balak, was indeed a mail carrier. However, the local priest had asked him to reply to my inquiry.

Interestingly, his mother knew the Fuchs family, because they had been neighbors. But he indicated no other German lived there except the Hoffmanns, who were not conversant in German. Balak enclosed a picture of himself on a horse-drawn sleigh in front of his house with other members of his family. He invited us to visit them, and wished us a joyous Easter.

I rushed back a letter in Polish requesting more information, along with American T-shirts for the children. Just days later I received a second letter, this time from the priest. Father Cazimir Cotalevici noted his limited use of German, but gave some valuable insights into Pojana Mikuli. There are currently about 250 families living there, of whom 150 are Polish and 100 Romanian. He stated that the German people were relocated back to Germany in 1940 with only three families, the Hoffmanns (headed by Rudolf, Otto, and Fridol) remaining. Homes vacated by the Germans were taken by Romanians from the country at large.

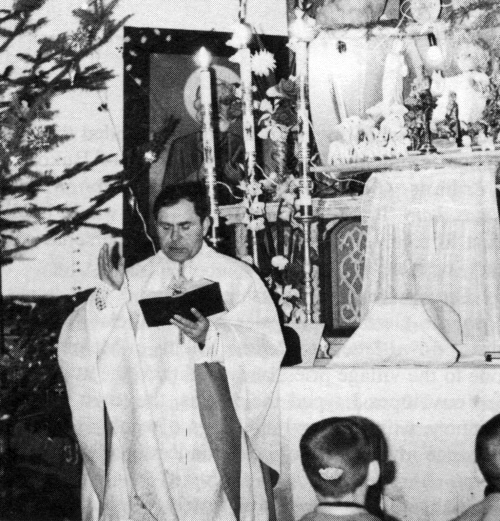

Fr. Cazimir noted that he is a Pole from Odessa, U.S.S.R., and has ministered with pleasure in Pojana Mikuli for the past twenty-two years. In June 1943 the original Catholic church was burned down, and today his congregation is not rich, but is very devout. He enclosed two pictures: one of the present church’s exterior and the other of himself conducting Christmas services.

I next received another letter from Balak, this time typewritten. He thanked me for my letter and the materials I had enclosed on Pojana Mikuli, which he noted, all had read with great pleasure. The villagers are occupied in agriculture, keeping cows, sheep, and other animals. The soil is not rich enough for crops other than potatoes and hay. The men work in the forest, cut the trees for timber and firewood. He could not help me with my request for records, because they were taken by the German occupation army. Moreover, on May 1, 1944, the entire village went up in flames.

Lukasz Balak wrote that his house is located on the place where Johann Fuchs previously resided, near the church. This he established from a plat of the town which I had sent him. He repeated his invitation for our family to visit him. He described their life as very modest. At last liberated from the communist yoke, they wish for justice, freedom, and dignity.

The letter of August 14, 1990 from Balak was hand written. He explained that he could not use the only typewriter in the village due to the absence of the priest, to whom it belonged. Their harvest was good and he sent another photo of his son, Fr. Cotalevici, and another unidentified priest serving first communion in July. The free practice of their religion is in stark contrast to the major population centers of Romania where suppression by the deposed Nicolae Ceausescu was the standard. In addition, the Ceausescu regime had embarked on a program to bulldoze the ethnic villages, moving the people to concrete agro-industrial centers.

The townspeople were able to have translated the literature I sent to them by visitors who brought medications and supplies. Among the materials I sent was a brochure of all Bukovina German organizations in the world. These were evidently passed on because I received a letter in September from a cultural organization in Suceava. They requested texts and papers about historical Bukovina to inform their many German members. These people are most likely descendants of the few Germans remaining after World War II.

After each letter I receive, I send a reply with news and pictures from America to stimulate another response from Mr. Balak, ensuring that our relationship continues. Most appreciated by my family, near Christmas of 1990, a letter written on December 9 by Balak also contained a religious card with a Christmas greeting and wish for a Happy New Year to us. He related that they were always very happy when a letter comes from me, and noted that my second parcel did not arrive. Only parcels from Germany are delivered, so I was advised not to send parcels, postal coupons, or other funds, as they are not honored in Romania. Mr. Balak went through a great deal of effort to honor a prior request, visiting area churches and cemeteries. He found only one grave marker with an ancestral name, an Erbert, dated 1890. Their parish prayed for them during All Souls Day. He found no church documents available and will no doubt be shocked to learn that I have since found these very records on microfilm at the Hays, Kansas branch of the L.D.S. Family History Center.

My return letters were to both Fr. Cotalevici and Mr. Balak to let them know of a scheduled visit to their area by two members of the Bukovina Society, Paul Polansky and Wilf Uhren. These men are part of a convoy bringing aid to our ancestral villages, within several miles of Pojana Mikuli. Certainly all will be met.

I share my personal letter writing experiences in order to encourage members of the AHSGR to write and establish contact with your ancestral villages. Although we have few, if any, relatives still residing in the old country, we might nonetheless make contact with people still there. This would serve the twofold purpose of facilitating our research endeavors and help those still living there improve the quality of their lives.