from Die evangelische Kirchengemeinde Neu-Zadowa und Nikolausdorf

von ihrer Gründung bis zur Umsiedlung 1883-1940, pages 40-46

by Edgar Müller

Irmgard Hein Ellingson, M.A, trans.

IV. Teil in der Schriftenreihe des Hilfskomitees der evangelischen Umsiedler aus der Bukowina

Druck: A. Gottliebs + J. Osswalds Buchdruckereien, Kirchheim/Teck, 1981.

(Part IV in the publication series of the Assistance Committee for Evangelical Resettlers from Bukovina;

printed by A. Gottliebs + J. Osswalds Buchdruckereien, Kirchheim/Teck, 1981)

Posted July 30, 2005

This little village, which was settled by German settlers mostly from Galicia in about 1892, lies about eight kilometers northeast of Neu-Zadowa[i]. The soil conditions are the same as in Neu-Zadowa. Its situation on the left bank of the Sereth River was profitable as long as the high water danger was not as frequent or acute, just as in Neu-Zadowa which was right on the Sereth.

The settlement was started with private initiative. Twenty-six settlers from Nadworna, Brettheim, Diamantheim, and Ugartsthal, all in Galicia, settled upon the estate of the Graf [a duke or earl] Nikolai Wassilko, for whom the community was named. They had chosen to move from Galicia, where their ancestors had settled, because they found no possibilities to secure work and bread for their children. Some moved from other Bukovina villages to try life in Nikolausdorf. These included the families of Wilhelm Hehn from Tereblestie, the Gerlieb family from Lichtenberg by Radautz, and others. Graf Wassilko’s offer seemed appealing. His mediator made many promises to the interested potential immigrants to make their decision easy. They were supposed to make their homes in the poor houses. They sold all that they had in Galicia and moved to Bukovina in the hope for a better future. This hope was soon disappointed as the promises of the mediator proved to be irrelevant. Some moved on, searching for another place to settle. Some went abroad to North America and to Canada.

The number of 170 residents remained constant throughout three decades. Those who stayed invested all their energy upon the improvement of the soil conditions by digging waterways. A comprehensive drainage system was finally completed in 1912 and then only with government assistance and the advancement of credit secured for the purpose by the Hypothekenbank in Czernowitz. So it was only right before World War I that the economic situation improved. This lasted a short time before the course of the war [translator’s note: World War I] had devastated all of the progress that had been made in the community.

The village school teacher Josef Hargesheimer wrote about the early time of the settlement in Nr. 16/925, page 248, of the Kirchlichen Blätter, a newsletter published by the Siebenbürgischen Landeskirche, or the Transylvania Provincial [Evangelical] Church[ii]:

“It was a dismal time. No crops, no earnings, only the most scanty nourishment and food in spite of all the diligence and the available and willing workers. There were many, very many, who only saw and relished bread on the festival days or holidays! The distress grew more and more, which finally led to a general indebtedness. Despair drove many of the disappointed to Germany or even to America where they hoped to carve out a better fate. The others, who remained loyal to their newly-gained homeland acquired by their own sweat, wrested a meager return from the swampy soil with dogged persistence and made a miserably bare living through a succession of years, but they stuck it out. The weathered Swabians[iii] looked up to heaven; in their impossibly unbearable afflictions, they looked in trust to God, who finally guided their life journey to a better path and granted them a bit of light as a sign of his protection. This they received with thanks and they began to make progress. This test lasted a long, long time but they persisted. But by the year 1911, the existence of the colonists was only humble. In rainy years, the swampy fields yielded scarcely more than what had been planted in them! Although seed and harvest in other areas had 1 to 7 or 1 to 8 ratios, here they only reached 1 to 3 or 1 to 4 yields in the best instances. All agreed that change was needed. United in their predicament, the colonists decided to drain their swampy fields. The work began in 1910 and was completed in 1912. This proved to be admirably worthwhile.

“Unfortunately the colonists could only see the fruits of this after the war because in the course of it, most of them had to leave their homes. But upon their return, their homes were not waiting for them: all the buildings had been sacrificed to the fury of war.”

World War I had ravaged the community. In 1914, the Cossacks came into Nikolausdorf, where they remained for three months. In the year 1916, practically all the people of Nikolausdorf had to flee and after much hardship, they reached Niederoesterreich [Lower Austria] where they and other refugees from the east found shelter in Neumark-Kalham. When the Russians were driven back again in 1917 and the people returned to their village, they found only one house that had been spared. All the houses had been burned to the ground with the exception of the house belonging to the Steinigers, an elderly couple who had not fled.

After World War I, the results of the soil drainage project were seen to be successful. Even if the yields were not even close to the normal harvest production, the existence of the tenacious remaining settlers was secured. To further develop this, additional sources of income were sought. For a time, it was profitable to haul wood to the nearby train depots in Lukawetz und Berhometh. Others resorted to dairy products. Philipp Hahn, Georg Steiniger, and Johann Schüttler, for example, bought cream and made butter that was in demand and brought good profits. Opportunities to make money were also offered by the big Landwehr[iv] sawmill. A machine that processed birch wood for matches was also located in Nikolausdorf.

All of this only resulted in an insignificant improvement of the economic situation. There was no possibility of expanding the community. So the population remained stable at about 200 until the resettlement in 1940.

School and Church

In this isolated location, it was a vital necessity for this small community to have its own school. They could not even think about a religious parochial school because many Polish and Jewish families had settled in the community at the same time. So with the help of the Gutsherrschaft, or manorial estate, a school was built in 1890 and handed over to the village’s civil administration. Until a fully qualified teacher arrived, a village resident by the name of Eilmes instructed the children. An orderly school operation was taken up with the arrival of the teacher Rudolf Rilling. He was succeeded by the teacher Gustav Rilling and then after World War I by Josef Hargesheimer, who remained until the resettlement. The Evangelical teacher also provided religious instruction.

The situation changed after 1918. The public school stood upon the Evangelical church ground but was supported by the Romanian government[v] which also provided for the necessary repairs. Although the school house had also served as the location for the Evangelical worship services since the village’s formation, this became increasingly difficult in the Romanian era. Permission from the appropriate civil inspector had to be obtained for church events that were held in the school. Furthermore the Evangelical teacher was subject to a Romanian regulation which specified that a German teacher could not be the headmaster of a public school. Because of this, the long-cherished dream for a church building was verbalized more and more often.

This hope was already alive before World War I when Pfarrer Lic. [Pastor] Max Weidauer served the village from Storozynetz. He applied to the Gustav-Adolf Verein[vi] in this letter dated 1 October 1925:

“To the most honorable board of directors of the Evangelical Association of the Gustav-Adolf-Stiftung in Leipzig.

“Most honored gentlemen! I would like to permit myself to present a small matter which is, however, very close to my heart. In the years in which I was stationed in Storozynetz, Bukovina, as a circuit pastor, the little community of Nikolausdorf also belonged to my pastoral care. An upright, quick-witted people built this Evangelical community. I had to give up my plan to unite the Evangelical villages of the Sereth valley in a self-supporting parish based in Storozynetz because of my relocation to Kolomea in 1914 but it gave me great joy when after the war, the communities took up that plan again and carried it out. My joy was also great that Nikolausdorf built its own church. The Nikolausdorf people have not been lacking in self-sacrifice, as I know from various sources and believe to be true of the faithful there. – Now I have received from there the news that so much is lacking that the dedication cannot take place this year unless some financial assistance is bestowed upon them. By virtue of my position, I may be prepared to effect this by a warm recommendation. I do not know if you, the respected board of directors, have already helped with the construction of this church but I will permit myself to forward the request from Nikolausdorf to you. If the board of directors itself can do nothing in this matter, perhaps the board might assist my Nikolausdorf people by means of a gracious recommendation to another organization. With great and grateful respect from Kolomea on 1 October 1925, [signed] Lic. Max Weidauer, pastor in Kolomea, chairman of the branch association for former Galicia.”

In the meantime, the community had already started the construction of the church in 1925. The competent people, who knew how to work with wood materials, had already unselfishly done a lot of the preliminary work. Assistance also came from the Bohusiewicz manorial estate which belonged to an old lady with a good relationship to Nikolausdorf. The community had the great help of the schoolmaster Josef Hargesheimer, who by every means possible sought friends with a heart for the church’s completion. The most assistance came again from the Gustav-Adolf-Werk. The first 300 Marks arrived in January 1926. From the thank-you letter, it can be determined that Karl Müller served as the Kurator or trustee, Johann Daum as the presbyter [council member], and Johann Hehn as secretary of the presbyterium [church council]. The church was already completed in 1925 and dedicated.

The joy did not last long. Three years later, on 19 July 1928, the congregation had to turn to the Gustav-Adolf-Zentralverein with news of misfortune. The church building had been so severely damaged by dry-rot that about 63,621 Romanian lei were needed for repairs. The community could not raise that kind of money by itself. The written request was signed by the trustee H. Wagner, the presbyter Friedrich Sauer, and Johann Hehn, secretary. Help was urgently needed. On 23 March 1929, the chairman of the Bukovina branch association, the Rev. Immanuel Gorgon in Illischestie, received a reply: “We are happy to inform you that in response to your recommendation dated 26 July 1928 on behalf of the Storozynetz parish office for the repair work on the little church in Nikolausdorf, we have authorized a sum of 300 Reichmark which will be forwarded to our organization’s office in Siebenbürgen. We ask that you inform the Storozynetz parish office of this and deliver to them the enclosed protocol dated 10 July 1928.” With this, the crisis was resolved. The Gustav-Adolf-Werk was approached once more for a gift to complete the decoration of the church. This consisted of a picture of Martin Luther and one of [his fellow reformer] Philipp Melanchthon as well as two proverbs or verses to be hung on the wall. These reached the congregation in a roundabout way through Siebenbürgen.

So the church construction was completed, inside and out. Ten years later, the resettlement extinguished all life in the village. Only the Poles and the Jews remained and later Ukrainians moved into the German houses, which were destroyed by the local people.

Organization as a Pfarrgemeinde, or Parish

This was essential for Nikolausdorf, as well as for the other villages in the Sereth valley. By 1902, Nikolausdorf was a preaching station for the Czernowitz parish. The worship service was conducted by the Evangelical teacher Rilling and then Hargesheimer, who were each compensated for this duty with .57 hectare of land and a small cash sum. The efforts for the establishment of a parish consisting of the Sereth valley communities with its base in Storozynetz, to which Nikolausdorf belonged, failed due to World War I and Pastor Weidauer’s relocation to Kolomea.

The joining of the Evangelical Church in Bukovina to the Siebenbürger Landeskirche made possible the proper church arrangements for the establishment of a united parish. Church life had progressed to the point that the congregation was now visited six to eight times per year by the resident pastor from Storozynetz and the pastor was more accessible for church matters. Earlier the pastor had to be brought from Czernowitz which happened only infrequently, due to circumstances. The first ministerial act for Nikolausdorf as recorded in the Czernowitz church books was: “Died 15 November 1899 in Nikolausdorf House #426, Jakob Zorn, carpenter, age 33 years, married to Auguste Mattheis, born in Ugartsthal in the year 1866.” Other church matters which had been handled by Orthodox priests were also entered in the church books.

Today the Nikolausdorf cemetery has been leveled. This was reported by a resident named Willi Hehn, who did not resettle [in 1940] and spent three years as a Russian soldier [in World War II].

Families were separated with the resettlement to Germany. The people left Nikolausdorf at the beginning of October [1940]. Those being resettled went to a reception camp in Bielitz, Silesia, from which they were relocated for the most part in the eastern parts of the German Reich. We give the names of those who died in the war, as far as they are known:

List of the Deaths in World War II

Gerlieb, Philipp, son of Philipp, born 1924

Gerlieb, Ferdinand, son of Philipp, born 1926

Hahn, Karl, son of Philipp, born 1926

Matthes, Philipp, son of Johann, born 1914

Merk, Edmund, son of Heinrich

Merk, Otto, son of Johann

Müller, Otto, son of Johann

Scheinost, Artur, son of Franz, born 1923

Scheinost, Franz, son of Franz, born 1920

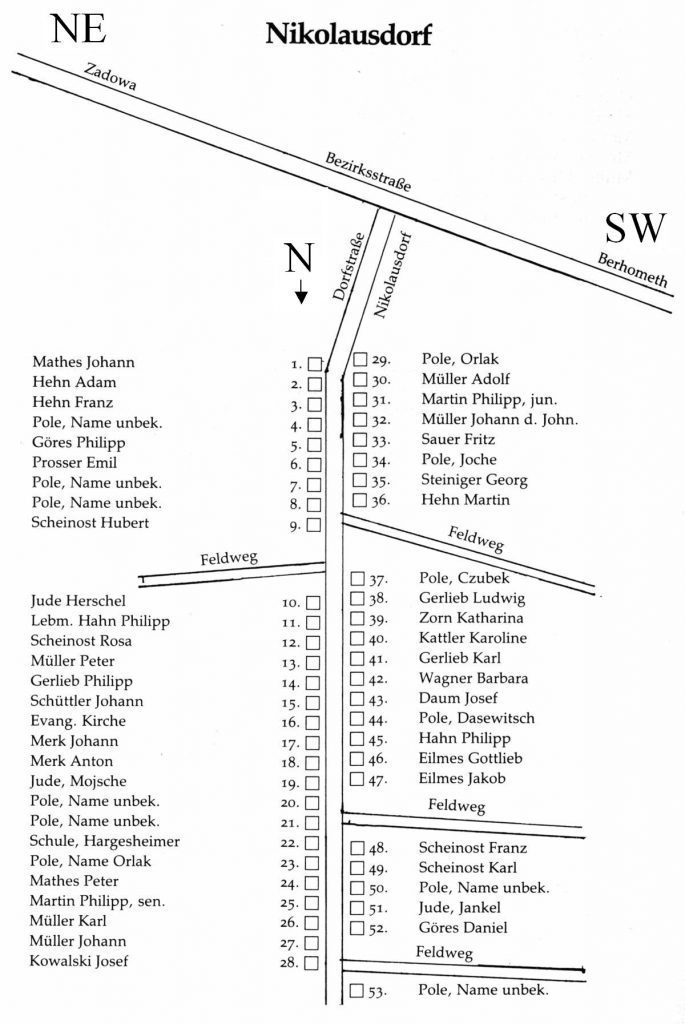

1. Mathes, Johann

2. Hehn, Adam

3. Hehn, Franz

4. a Pole whose name is unknown

5. Göres, Philipp

6. Prosser, Emil

7. a Pole whose name is unknown

8. a Pole whose name is unknown

9. Scheinost, Hubert

crossing a Feldweg or field lane

10. a Jew named Herschel

11. Hahn, Philipp

12. Scheinost, Rosa

13. Müller, Peter

14. Gerlieb, Philipp

15. Schüttler, Johann

16. Evangelical Church

17. Merk, Johann

18. Merk, Anton

19. a Jew name Mojsche

20. a Pole whose name is unknown

21. a Pole whose name is unknown

22. the school and the teacher Hargesheimer

23. a Pole by the name of Orlak

24. Mathes, Peter25. Martin, Philipp Sr.

26. Müller, Karl

27. Müller, Johann

28. Kowalski, Josef

29. a Pole named Orlak

30. Müller, Adolf

31. Martin, Philipp Jr.

32. Müller, Johann, son of Johann

33. Sauer, Fritz

34. a Pole named Joche

35. Steiniger, Georg

36. Hehn, Martin

crossing a Feldweg or field lane

37. a Pole named Czubek

38. Gerlieb, Johann

39. Zorn, Katharina

40. Kattler, Karoline

41. Gerlieb, Karl

42. Wagner, Barbara

43. Daum, Josef

44. a Pole named Dasewitsch

45. Hahn, Philipp

46. Eilmes, Gottlieb

47. Eilmes, Jakob

crossing a Feldweg or field lane

48. Scheinost, Franz

49. Scheinost, Karl

50. a Pole whose name is unknown

51. a Jew named Jankel

52. Göres, Daniel

crossing a Feldweg or field lane

53. a Pole whose name is unknown